Default Alive and Free Cash Flow

The Playbook for Today's Environment

The Digital Leader Newsletter — Strategies and Techniques for Change Agents, Strategists, and Innovators

What on earth is The Digital Leader Newsletter doing talking about free cash flow??? It’s a fair question and a topic that just a couple of months ago, I would not have forecasted. The economy has shifted (understatement?), and if my ethos is to “listen to your customers”, then I need to listen to my customers & the market and adjust with it. Don’t fear! Our typical menu of customer-centricity, reducing friction, and succeeding at digital transformation will be back, but this week the menu consists of free cash flow, what it is and why it matters in a business and investing cycle like the one we are in.

One of my favorite podcasts is The All-In Podcast. The four hosts have serious operating and investing experiences wrapped in discourse and banter is what the four “besties” bring to every week. At ~ minute 36 of this week’s episode 83 from Thursday, May 26th, they discussed free cash flow and being “default alive”. 1

Chamath Palihapitiya (CEO of Social Capital, billionaire, owns ~10% of the Golden State Warriors)

There are a lot of companies that are going to have to get religion on free cash flow conversion ASAP…Most CEOs, to be very blunt, are poorly educated so their level of numeracy to even understand this is pretty poor.

As the All-In-Podcast discusses, you need to have a plan (and likely put it in action) where you cut costs to the point where you are FCF positive — you are default alive.

So let’s improve our level of “numeracy” and dive into free cash flow!

What It Is and Why It Matters

Tom Alberg, the founder of Madrona Venture Capital and a board member at Amazon for 21 years wrote the foreword for The Amazon Way. In his foreword, he writes

Lots of software companies tout their high-profit margins, sometimes running at 80 percent or more. Bezos has always argued that free cash flow is more important, not only because the physical retail business is a low margin business, but because as he says “percentages don’t pay the light bill, cash does!” On a macro scale, he would ask “Do you want to be a $200 million company with a 20 percent margin or a $10 billion company with a 5 percent margin?” In fact, this is how Amazon has grown, by emphasizing investing for free cash flow or cash margins rather than percentage margins or short-term earnings per share. Amazon’s quarterly earnings press releases always led with the amount of cash flow growth – although stories in the press always headlined whether Amazon had gained or lost a few cents per share. And the way Amazon maximizes the growth of free cash flow is by rigorously focusing on inputs rather than outputs. Rossman justifiably includes an Appendix which goes into considerable detail on free cash flow and Amazon’s unit economic modeling which allows employees to understand how different buying decisions, process flows, fulfillment paths, and demand scenarios would impact FCF. Every student of business should read it.

So here’s Appendix C from The Amazon Way. My former Amazon colleague and friend Randy Miller largely wrote this appendix.

A Primer in Free Cash Flow

Mass retail is a notoriously low-margin, efficiency-based business. Keeping large margins over a long period is difficult and likely results in a smaller market share. From the beginning, Amazon has set a course and vision to be “the biggest store in the world,” starting as a bookstore and now including all categories. Tied to this philosophy is a perspective on optimizing financial results. Jeff Bezos sums up this strategy, "Percentage margins are not one of the things we are seeking to optimize. It's the absolute dollar-free cash flow per share that you want to maximize. If you can do that by lowering margins, we would do that. Free cash flow, that's something investors can spend."

Free Cash Flow Defined

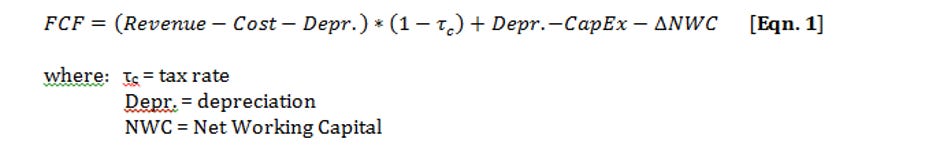

Free cash flow (FCF) can be calculated in a few ways, with most calculation methods designed for investors who are looking to untangle the accounting tricks used to generate financial statements. For the business manager, we will focus on the following definition:

[Note that depreciation is added back in because it is a non-cash expenditure. It is for this reason that FCF is not the same as other measures commonly used by investors to evaluate the health and success of a business, such as EBITDA, net earnings, and profit margin percentage.]

Rearranging terms in Eqn. 1, we arrive at a basic definition of free cash flow:

“Revenue – Cost” represents cash generated from operations. CapEx and ∆NWC are the money spent to keep the business running, and the final term in Eqn. 2 is the cash contribution that “depreciation as a tax shield” represents.

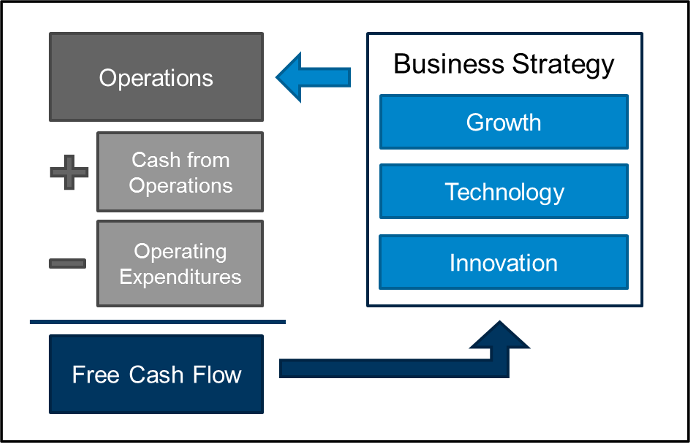

A business’s day-to-day operations, such as the sale of products or services, are the source of FCF, and operating expenditure is cash spent to run and maintain the business on a day-to-day basis. FCF, however, is the remaining cash available and is free to be spent in ways that add value to the business. Stated simply, FCF is free to be spent in ways that grow real value for shareholders.

In his 2004 Letter to Shareholders, Bezos explains the reason for Amazon’s focus on FCF: “Why not focus first and foremost, as many do, on earnings, earnings per share or earnings growth? The simple answer is that earnings don’t directly translate into cash flows, and shares are worth only the present value of their future cash flows, not the present value of their future earnings.”

Our ultimate financial measure, and the one we most want to drive over the long term, is free cash flow per share.

Free Cash Flow as Amazon’s Business Engine

Free cash flow can be a powerful engine for driving shareholder value. At Amazon, it is both the proverbial North Star that managers use to guide operations and the fuel that leadership uses to drive business strategy.

The following figure shows how FCF moves from operations to business strategy, which in turn grows and improves operations.

Figure B-1. Free Cash Flow as a Business Engine

Operations Generate Free Cash Flow. Now that we’ve established that operations are the source of free cash flow, the next step is to set up appropriate measurements and KPIs. A few examples from Amazon include contribution profit and total sales rather than contribution margin as a percentage.

This focus on FCF as the primary financial measure at Amazon began in earnest when Warren Jenson became CFO in October of 1999. As noted above in Jeff Bezos’s quote, it is also the time when the Amazon finance organization began to move away from a percentage margin focus to a cash margin focus. Bezos loved to toss out the axiom “percentages don’t pay the light bill, cash does!” He would then ask, “Do you want to be a $200 million company with a 20% margin or a $10 billion company with a 5% margin? I know which one I want to be!”

This new direction of putting FCF at the center of Amazon’s strategy, as well as the need to manage it successfully, drove the creation of powerful measurement and modeling capabilities. One powerful example of this is the robust and extremely accurate “unit economic” model that was developed. This tool allows merchants, finance analysts, and optimization modelers to understand how different buying decisions, process flows, fulfillment paths, and demand scenarios will affect a product’s contribution profit. This, in turn, gave Amazon the ability to understand how changes in these variables would impact FCF and has allowed them to react accordingly.

Very few retailers have this type of in-depth financial view of their products, and thus have a difficult job truly making decisions or building processes that optimize the economics. Amazon uses this knowledge to determine the number of warehouses they should have and where they should be placed, to quickly assess and respond to vendor offers, to develop a better understanding of inventory margin health, to know how much it will cost them to hold a unit of inventory over a specified period of time down to the penny, and so on.

Free Cash Flow as the Fuel for Business Strategy. Let us now assume that operations are running efficiently and FCF is being generated. As a leader, it is your responsibility to spend this cash in whatever way creates the most value for shareholders. Your options fall into four basic categories:

Investing in growth

Paying down debt

Buying back shares

Paying out dividends

Investing in growth is the most interesting option here and has been the core of Amazon’s business strategy to date. Bezos believes that a company will stagnate without constant innovation and that the primary ingredient for strong innovation is free cash flow. Many would argue that spending FCF on buying back shares or paying out dividends is a signal that senior leadership has run out of positive NPV projects and that shareholders are better off finding better uses for their money.

At Amazon, common areas of investment have included adding new categories, new businesses, new infrastructure (such as fulfillment centers), and scale through technology. New businesses are incubated for a period of time in order to prove their viability and optimize operations before FCF is invested to scale to a national or global level. Amazon Fresh is a perfect example of this; it was run locally in Seattle since 2007 before expanding to other cities in 2013.

Free Cash Flow as a Decision Driver

As a business leader, one of your main responsibilities is to make sound and reasonable decisions for the management of your company. It’s a given that these decisions should be based on data, goals, KPIs, and competitive insights, but which ones? Let’s take an in-depth look at how a C-level decision can vary with the following two goals:

Maximize Net Earnings

Maximize Free Cash Flow

To compare these alternative decision drivers, let us analyze a hypothetical business scenario from Jeff Bezos’s 2004 Letter to Amazon Shareholders2:

Imagine that an entrepreneur invents a machine that can quickly transport people from one location to another. The machine is expensive—$160 million with an annual capacity of 100,000 passenger trips and a four-year useful life. Each trip sells for $1,000 and requires $450 in cost of goods for energy and materials and $50 in labor and other costs.

Continue to imagine that business is booming, with 100,000 trips in Year 1, completely and perfectly utilizing the capacity of one machine. This leads to earnings of $10 million after deducting operating expenses including depreciation—a 10% net margin.

Although overly simplified, this business scenario allows us to take a closer look at the decision process.

Maximize Net Earnings. It is now the end of Year 1, and the entrepreneur must make a decision. If the company’s primary goal is to maximize earnings, then the best course of action is to invest more capital to add additional machines, fuel sales, and grow earnings. Let us assume that the entrepreneur decides to grow the business by 100% each year, purchasing an additional machine in Year 2, two more in Year 3, and four more in Year 4.

Here is the income statement for the first four years of business when earnings growth is the company goal:

Table B-1. 2004 Letter to Shareholders

If this transport machine is truly revolutionary, it is reasonable to assume that demand can keep up with capacity. In the first four years of operation, the company sees 100% compound earnings growth and $150 million of cumulative earnings! It appears that the sky is the limit for this company. Let’s see what things look like when maximizing FCF is the goal.

Maximizing Free Cash Flow. To analyze this business through the free cash flow lens, let’s take a look at the cash flow statement for Years 1 through 4 with the additional machine purchases included:

Table B-2. 2004 Letter to Shareholders

Free cash flow tells a very different story from the one told by Earnings. FCF is negative in Year 1 because of the massive capital expenditure on the transport machine. The machine is already being run at full capacity and only has an operating life of four years, so even with 0% growth, the net present value of cash flows (assuming 12% cost of capital) is still negative.

To improve FCF, we can focus on improving cash from operations or on reducing operating expenditures. Probing in these two areas leads to questions such as:

How much would the production cost of the transportation machine need to be reduced for this to be a positive FCF business?

How much should the price of a ticket be raised for this to be a positive FCF business? What is the price elasticity of near-instant transportation?

Would the transportation machine last longer if it wasn’t run at full capacity? What if it turned out that running at 80% capacity doubled the operating life of the machine? How would this affect FCF?

With maximizing FCF as the goal, our manager would have made very different investment decisions than when maximizing earnings was the goal. Without other options or modifications to this business model, we see that, in this scenario, committing capital to growth is a poor choice. Rather than investing in growth, the best course is to invest in improving and optimizing the business model to see if this business model can become FCF positive.

Summary

In this economic environment, evaluate your strategy and goals. Evaluate being “default alive”. Default alive requires you to be free cash flow positive. Simple — be making more cash than you are spending. This gives you the best position for future negotiations and investments.

Onward!

John

About The Digital Leader Newsletter

This is a newsletter for change agents, strategists, and innovators. The Digital Leader Newsletter is a weekly coaching session with a focus on customer-centricity, innovation, and strategy. We deliver practical theory, examples, tools, and techniques to help you build better strategies, better plans, and better solutions — but most of all to think and communicate better. You’ll be able to follow up with questions and advice.

https://www.allinpodcast.co

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1018724/000119312505070440/dex991.htm

Great post John!